“Diversification is a protection against ignorance. It makes very little sense for those who know what they’re doing.” Warren Buffett

I’m reasonably certain Warren Buffett did not intend to disparage anyone with that quote. We’re taught at an early age “never to put all your eggs in one basket” because it makes perfect sense for many things in life. If you put all your efforts and resources into one area, you could lose it all. In investing, we call it “diversification.” Broad diversification makes sense for many investors who have neither the time nor inclination to actively manage their portfolio. So, investing in an index fund might provide them with the comfort of lower risk and volatility.

When Buffet spoke those words, he was referring to investors who choose to manage their own portfolio, attempting to outperform the indexes. His point is, if investors know what they’re doing in constructing a portfolio, there should be no need for diversification. If your investment selection is based on what they know about a company—how it makes money, the reliability of its cash flow, how it uses its cash flow, how it invests its capital, and the strength of its management—why the need to diversify?

Why Investors Diversify

Generally, investors diversify because they want to manage risk. Risk-averse investors tend not to like volatility. Volatility is a particular type of risk having to do with the excessive increase or decrease of stock prices. Diversification is a way to reduce volatility by combining uncorrelated assets in a portfolio. It’s investors’ acknowledgment that it’s impossible to know which assets will outperform other assets at any given time. The goal of diversification is to reduce that risk. But is that a worthy goal?

Volatility is not the Risk You Think it Is

While extreme volatility can be scary, it’s what drives returns. Throughout the history of the stock market, stock prices have gone up, and they’ve gone down. But, as we experienced last year, steep stock market declines have always led to steep stock market gains, and, as history shows, the gains have always been significantly more extensive than the declines.

When you view volatility through that perspective, it turns out to be nothing more than noise. Volatility is only a risk if you experience a permanent loss of capital, and that can only happen if you sell during a market decline. If you choose the wrong stock, you are more likely to experience a permanent loss of capital.

How Many Stocks Should You Own?

So, if the goal is to avoid a permanent loss of capital, how should you construct your portfolio? How many stocks should you own? If it were up to Buffett’s partner, Charlie Munger, it would just one company—but it would have to be the right company. As he put it, it’s easier to be right with one company in which you have complete confidence in its future than to be right with 30 or 40 companies. If you can select one company with a solid balance sheet, dependable earnings, and smart management, you most likely don’t have to worry about a permanent loss of capital. High-quality companies are better able to withstand the headwinds of a temporary macro-event such as a global pandemic.

But things happen and, even the best company can run into unexpected trouble, so it makes sense to own a few more. How many more? The real question is how many stocks an investor can manage in terms of having high conviction in their value and capacity to grow. By owning 30 or 40 or 70 stocks, you could actually be setting yourself up for a permanent loss of capital because it is difficult to know everything you need to know about all those companies. For us, the sweet spot has been ten to 15 stocks, which is just enough diversification to allow us to sleep at night but few enough to know everything we need to know about them to avoid a permanent loss of capital.

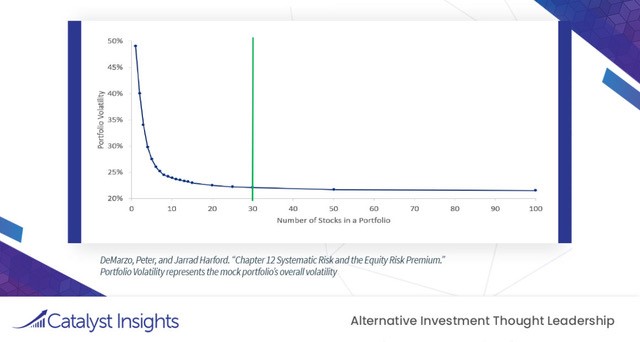

Regarding volatility, it takes fewer securities to achieve optimum diversification than most investors realize. As the following chart shows, volatility decreases as you add stocks to your portfolio, which makes sense. As you can see, volatility all but disappears at 30 stocks, which is why many investing experts say that 30 is the optimum number to achieve proper diversification. I would argue that while 30 is nearly the terminal point of the decrease in volatility, it’s not optimum. The most significant bend in the curve occurs between ten and fifteen stocks, after which the reduction in volatility is negligible.

To me, that diminishing benefit of diversification just doesn’t warrant adding more stocks if I don’t have to. That becomes diversification just for the sake of diversification, which, as Buffet says, doesn’t make sense. If you do your homework and adhere to an investment process, you can keep it at ten to 15 by choosing great companies at great prices, making them great investments with little likelihood of any permanent loss of capital.